In the previous article, we explored the Orthodox Church’s inheritance of iconography from ancient Israel. Today, we

will consider three-dimensional iconography in both Israel

and the Church.

The Orthodox Church is rich with icons, both 2D and 3D.

Three-dimensional icons can be traced all the way back to the Tabernacle and the Temple in ancient Israel, and their beauty continues to the present day within Orthodox Christianity.

The word “icon” comes from the Greek word “εἰκών”,

which simply means “image”. An icon can be either a two-dimensional image (portrait), or a three-dimensional image (statue).

In ancient Israel, during the time of Moses, God commanded His people to fill the Tabernacle with icons of angels, both 2D and 3D. The Ark of the Covenant was adorned with three-dimensional cherubim, while two-dimensional images of angels were woven into the tapestry.

Approximately 1000 years before the birth of Christ, the first Temple in Jerusalem was built by King Solomon. This holy construction project included some impressive golden statues:

Inside the inner sanctuary, he made two cherubim standing majestically, each ten cubits high. One wing of the cherub was five cubits, and the other wing of the cherub, five cubits. It was ten cubits from the tip of one wing to the tip of the other. The other cherub was ten cubits; both cherubim were of the same size and shape. The height of one cherub was ten cubits, and so was the other cherub. Then he set both cherubim inside the inner room; and they stretched out the wings of the cherubim, so the wing of one touched one wall, and the wing of the other cherub touched the other wall. Their wings touched each other in the middle of the room. He also overlaid the cherubim with gold. (3 Kingdoms 6:22-27. The Orthodox Study Bible

[p. 395]. Thomas Nelson. Kindle Edition.)

When we fast-forward to the Christian era, we learn that three-dimensional iconography persisted into the early Church. Eusebius, a fourth century Church historian, tells us that outside the house of the woman in the Gospels with a hemorrhage cured by Christ was “a bronze statue of a woman, resting on one knee and resembling a suppliant with arms out stretched. Facing this was another of the same material, an upright figure of a man with a double cloak draped neatly over his shoulders and his hand stretched out to the woman.” Eusebius says, “This statue, which was said to resemble the features of Jesus, was still there in my own time, so that I saw it with my own eyes” (Church History, Book 7, Chapter 18).

As Fr. Les Bundy has noted, the Seventh Ecumenical Council’s decrees on icons refer to all religious images, including three-dimensional statues. He also points out that Professor Sergios Verkhovskoi, conservative professor of dogmatics at St. Vladimir’s Seminary, affirms that statues are fully Orthodox, and are canonically equal to paintings in every way.

Fr. Les Bundy has also noted that statues were common in Byzantium. One of the most striking images originating from Constantinople is a 10th-century statue of the Virgin and Child. Constantinople was filled with statues, both inside and outside the churches. One author claims that over three hundred classical statues adorned the plaza before the Hagia Sophia.

The balance between 2D and 3D icons was affected in the 8th and 9th centuries, during the iconoclastic controversy. The iconoclasts were heretics who opposed the existence of holy images. Whenever they discovered Christian images of any kind, they commonly broke, effaced, or destroyed them.

As a result, Orthodox Christians frequently hid the images away, in order to protect them. Of course, it is easier to hide a few flat icons under your cloak, than it is to hide statues. So compared to the two-dimensional icons, few statues survived the iconoclastic attack. And even after the empire legalized icons once again, statues remained more costly to create than flat icons, thus keeping them relatively rare.

Tensions between East and West served to further complicate matters. While holy statues made a full comeback in the West, the East increasingly sought to distance itself from anything perceived as “Western”. After the events of 1054

and the subsequent Crusades had rendered the Great Schism complete, anything thought to be uniquely Western was assumed to be heretical. And since holy statues at this time were more common in the West than in the East, some Easterners mistakenly assumed that statues were unorthodox. This perception has unfortunately persisted among some groups of Orthodox Christians even to this day. Hopefully, an honest look at Orthodox Church history will help to clear up any misconceptions.

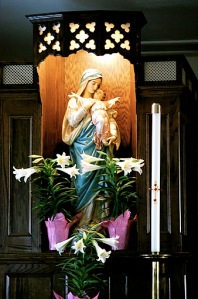

3D icon of the Virgin Mary with Christ Child – Holy Incarnation Antiochian Orthodox Church – Lincoln Park, MI

Thankfully, holy statues have survived in Orthodoxy. Centuries after Rome departed from the Church, a number of Orthodox churches kept three-dimensional iconography alive. Examples of such statuary include a 14th-century Serbian statue of the Theotokos and Christ Child, and a wood-carved statue of St. George found in a church in Greece. Other examples include an Orthodox statue of St. Nicholas of Mozhaisk, a semi-3D iconostasis in St. Isaac’s Cathedral in Russia, and a statue of St. Nicholas in an Orthodox Church in Demre, Turkey.

There are a significant number of modern Orthodox churches which are embracing their heritage via three-dimensional Orthodox iconography. Here to the right is a beautiful Orthodox statue of the Virgin Mary with Christ Child. It is currently in the sanctuary of the Holy Incarnation Antiochian Orthodox Church in Lincoln Park, Michigan. I visited there myself this past spring for Pascha services, and was quite delighted by the entire experience. I am thankful that God continues to inspire His faithful servants to create beautiful and holy icons, whether they be 2D, or 3D.

Good post

Yes – to live a TRUE Orthodox life. Not people’s creations of what THEY think is an Orthodox life! Statues are NOT icons. You are blinded and deceived. Jesus Christ, our Lord and God and Savior came to earth 2011 years ago to give us a chance to be saved. Christ also came to correct people’s wrong way of thinking and living. For one, He gave us the New Testament, and the Gospel – God’s Word, His Teaching – for us to follow. God’s Word stands all time and is Eternal Life. That statue of yours is NOT Orthodox and is NOT the Holy Mother of God. The Holy Mother of God only became the “Mother of God” when She gave birth through the Holy Spirit to Christ 2011 years ago. Read the New Testament!!

Did you even read at this post? Clearly 3d images exist in Orthodoxy…

Exactly. Eusebius wrote about a statue, dating from the Apostolic age, of the woman who had been healed of her internal bleeding, and of Christ extending His hand to her. The previous post in nonsensical and clearly refuted by this article (and other evidence of 3-D icons, like the ancient brazen serpent, the Cheruvim on the Mercy Seat/Ark of the Covenant, etc.)

THank you very much for this interesting and informative article, which confirms what i had suspected to be true: Eikon means image, whether two- or three-dimensional, and, just as both types of image were found in the jewish temple in Old Testament times, so have both types been sanctioned by oecumenical councils, and both types are to be venerated by orthodox and catholic christians.

As far as I know, the canons of the VIIth Ecumenical Council don’t distinguish between panel icons and statuary, or forbid three-dimensional images. Though with all due respect, I find unconvincing Fr. Bundy’s argument that few statues survived Byzantine iconoclasm because they were harder to hide! The only pre-iconoclastic panel icons we have (at least that I know of) are from two places which resisted the iconoclasts (Rome) or were out of their reach (Sinai). Yet a dearth of models-at-hand did not keep (two-dimensional) Byzantine iconography from blossoming.after the victory of Orthodoxy in the 9th century..

Statues of shepherds were common in the ancient world, and Apollo was often depicted as one. Such statues were convenient ways for early Christians to honor Christ the Good Shepherd, without giving away their secret belief to the neighbors. Likewise, Christ was sometimes depicted as a lamb, though there are no records of a three-dimensional image being made for Christian prayer. ( Perhaps this would have looked too much like worshipping a golden calf for the comfort of new Jewish converts?! Gradually, the iconographic tradition grew and was standardized; ultimately the struggle with iconoclasm strengthened and purified it.

Three-dimension images always were something of an exception and even a curiosity in the Christian East. For example, the Sinai Monastery escaped the ravages of iconoclasm, and its celebrated icon treasury preserves some of the few pre-7th century panel icons still in existence. But if there ever were any examples of devotional statuary there, they have not survived.

Likewise, three-dimensional icons existed historically in Orthodox Russia. Visitors to the Moscow Kremlin can find a whole roomful of them in the sacristy of one of the cathedrals (St. Michael’s?). Again, they were something of an exception.

Some of the examples linked to in the article above are red herrings, though I’m sure not meant to be by the author. St. Isaac’s Cathedral is an architectural copy of St. Peter’s in Rome, complete with stained glass windows. Perhaps as interesting is the baroque iconostasis done by Bernini for the (Greek-rite Uniate) Grottaferrata Monastery near Rome. Both churches are curiosities, not models for imitation.

The statue of the Madonna shown from the Michigan western-rite parish is an example of something that would have been typical in Roman Catholic churches several decades ago. But it would not have been accepted as canonical art in any church, east or west, before the Schism. I say this, not because of any lack of beauty in the image, but because of the sentimentality and emotion which the image conveys and which it invites the viewer to share. Nor is my saying this simply another example of “eastern” prejudice. Serious-minded Roman Catholics have struggled with the question of creating a properly sober, liturgical art: the Beuronese School is one attempt by western Christians to re-articulate (for modern times) the faith expressed in their own early medieval art.

Some have said that the ambiguous attitude of the Orthodox East to these images in practice is part of our theological reflection on the VIIth Council.. If the icon is to serve as a “window” (sorry for the cliche!), as a vehicle through which we enter into communion with the subject depicted, the physicality of the three-dimensional object runs the danger of (idolatrously) keeping one’s attention focused on the image itself. To pray before an idol is to pray to one’s own imagination, and so to pray to one’s self (if not to someone much worse).

If three-dimensional liturgical art is to find a place in Orthodox Churches, we will have to think through – and pray through – this question for a while. Simply ordering up from the catalogue of a local Roman Catholic supply house is a poor stopgap with unforeseen side effects. Liturgical statuary was always at the fringes of Byzantine iconography, and the living tradition of Orthodox western liturgical statuary has not been preserved except in museums and in isolated examples, but has been replaced by newer statues reflecting the spirituality of later, post-schism Catholicism.

How ironic that this discussion is taking place at a time when many western Christians are re-discovering the spiritual power of the Orthodox icon. My brother-in-law just returned from a trip to England saying that the C. of E. churches there are full of icons, and with vigil lights in front of them – much to the dismay of his Anglican wife! What do these people know that some of our Western-rite Orthodox do not? Perhaps the words of St. Paul, written in another context, can apply here: “all things are lawful, but not all things are profitable”.

IN the Church of the Great Lavra at Sankt-Peterburg in Russia, there is a three dimensional Crucifix flanked by three -dimensional statues of Our lady and Saint John the Evangelist, with candles burning before it. Besdies this example, i have seen three -dimensional Crucifixes in many many Eastern orthodox churches in diverse lands. As ofr Roman Catholic statuary, it is making a comeback in many places, after the parenthesis of iconoclasm affecting the Catholic Church for several decades after the Second Vatican Council. If God Himself ordered the statues of Cherubim to be placed within the Sacntuary of His temple in Jerusalem, i don’t see how anyone can object to our placing of holy statues in our churches today. Whether two- or three-dimensional, a sacred image is sacred because of the Sacred Personage which it stands in for, and to Whom it is consecrated: It seems really to be only a matter of cultural preference, not of theology. I personally do not appreciate cheap reproductions of icons – usually the most primitive-looking ones, alas – replacing native holy pictures and statues in Roman-rite churches, for example …

It was stated: “The statue of the Madonna shown from the Michigan western-rite parish is an example of something that would have been typical in Roman Catholic churches several decades ago. But it would not have been accepted as canonical art in any church, east or west, before the Schism. I say this, not because of any lack of beauty in the image, but because of the sentimentality and emotion which the image conveys and which it invites the viewer to share. ”

Well thank God there are no sentimental ikons to be found in Byzantine-rite Orthodox churches! And since my grandparents donated funds to help purchase the statue in question, I am sorry that they were such groveling peasants that their taste does not measure up to this posters.

It was further said: “My brother-in-law just returned from a trip to England saying that the C. of E. churches there are full of icons, and with vigil lights in front of them – much to the dismay of his Anglican wife!”

Yes, eastern folklore is very, very popular amongst the same crowd that loves a women vicaress in gothic style vestments.

One suspects that this sort of bigotry is going to remain imbeded in the Byzantine church regardless of the historical reality. One has to ask is the semi-iconoclasm simply anti-western bigotry, or a reflection of the level of islamification of the Byzantine church?

Interesting debate. I have heard many arguments both ways, some saying that the art of icons/images/statues etc should be assessed based on its “salvific” character: whether it tends to bring one closer to God, or to put up barriers to communion with God. Of course, how does one assess such character? In a fallen world, what man or woman can so judge? Even common sense ideas can find themselves challenged. Black Jesus? Is this really so different than blond haired, blue eyed Jesus? 16th century Italian style icons? Icons in the style of Iranian art? Post-modern, industrial style icons that “relate” to cultures that are largely ignorant of how the depicted saints dressed or looked?

It seems the least uncertain approach is conservative, and appealing to tradition.

If there are to be sanctioned “3D” Icons in the Church, they would need to follow the same canonical guidelines as “2D” Icons. “Realistic” (i.e. worldly) statues don’t fit that qualification, as true Icons show Saints as they truly are – glorified humanity in union with God – not as they were on this earth. They are windows into heaven, not “art” or “sentimental” portraits. Just a few thoughts.

Pingback: Holy of Holies | The Orthodox Life

Greetings Fr. Gleason, I was wondering if you could help guide me into a proper understanding of man’s relationship with the angels; first allow me to prime my questions in this manner:

‘The Cherubic Hymn is the primary cherubikon, or song of the angels, sung during every Divine Liturgy of the year…’

The words of the Cherubic Hymn are as follows:

“We, who mystically represent the Cherubim,

And chant the thrice-holy hymn to the Life-giving Trinity,

Let us set aside the cares of life

That we may receive the King of all,

Who comes invisibly escorted by the Divine Hosts.”

The Cherubim belong to the first hierarchy. It is said that God’s wisdom passes down through them unto man & granting him the spiritual sense of seeing the Lord.

And its probably no mistake that Solomon had images of them above the ‘mercy seat’, as your image reveals above.

So my question is this, what is the most respectable manner to invoke these Angels through prayer? As a priest, do you ‘mystically represent the Cherubim’ or is this some kind of metaphor and how so? If these high ranking beings are 2nd to the Seraphim, shouldn’t they be the ones to represent the faithful of mankind, rather than the faithful representing them as it suggests in the Cherubic Hymn? And finally, how might one learn the official roles and responsibilities of all nine levels of the Angels without trespassing or offending these spiritual entities and are Christians encouraged to also extend their search for knowledge of these majestic creatures outside of scripture and if so, what books might one seek out?

Thank you kindly for taking the time and energy to be a minister through this online medium. Now in the event that you find yourself without the ability or resources or time to give reply to my plea, could you have another intercede on your behalf?

Warm regards,

JY